Shut but still open: Spot check reveals Nairobi clinics still operating after official closure

In a major crackdown in December 2024, authorities inspected 466 health facilities in Nairobi, shutting down 117 clinics and arresting 15 individuals for operating without licenses.

As I walked through one of Nairobi’s neighbourhoods, conducting a spot check on health facilities listed as closed, I found myself outside a clinic that, according to the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council (KMPDC), had been officially shut down. The listed reasons included a lack of personnel—there was no one present to attend to the inspection team —and the owner was suspected of having fled.

Yet here I was, standing in front of its wide-open doors, just a day after it had been closed. There was no visible notice or signage indicating to the public that the facility had been shut down.

More To Read

- Ambulance operators, emergency personnel directed to register with KMPDC by September 15

- Union demands full implementation of Ruto’s directive on UHC staff absorption

- Kituo Cha Sheria moves to court over suspension of inmates’ medical services

- Relief for 633 doctors as Health Ministry approves postgraduate fee payments

- New Bill proposes Sh50 million fine for hospitals failing on patient safety

- UHC row escalates as governors accuse Ministry of Health of undermining devolution

A man sat just outside, looking relaxed, almost as though he were waiting for someone. He wasn’t wearing a white coat or any uniform that would hint at professionalism. I asked him if the doctor was around. Without hesitation, he reached into his pocket, pulled out a ring of keys, and unlocked one of the interior doors, inviting me in for treatment.

Inside, the sight was grim.

Shelves that should have held medicine were bare. A plastic bin filled with uncollected garbage sat by the entrance. The walls were dusty, and the smell of antiseptic was absent. Nothing about the facility felt sterile, safe, or remotely medical.

The man who had welcomed me introduced himself as Steward. He told me he had purchased the facility four months ago and was trying to get it up and running again.

"We operate on demand," he said plainly. "Those who know us come and we treat them. The hospital was well stocked before, but now we are just getting by."

When I asked if he knew authorities had shut the clinic down, he nodded. "Yes, they said it was a licensing issue," he replied, brushing it off as though it were a technicality.

But according to KMPDC records, the facility had been shut down not merely for licensing problems, but because no one had been available to meet the inspection team during a site visit. The official report suggested the owners had abandoned the place.

One man show

Now, Steward seemed to be running things alone—one man, a dusty room, and the trust of anyone desperate enough to walk in.

To understand more, I spoke with locals who live nearby. Most of them had no idea who actually owned the clinic. They simply noticed that the doors were always open, and that people still went in.

Many, however, said they had stopped visiting the facility. The lack of medication, the absence of equipment, and the general uncleanliness had made them uncomfortable.

"I went once, but they had no medicine. And the place looked dirty," one resident told me.

Steward, the assumed owner, claimed he had been away when the closure took place and insisted he had since resolved the licensing issue.

But when I pressed further—pointing out that the facility wasn’t even closed for a license lapse—he gave a response that was as bold as it was worrying. "On the ground, things are different. Even if they find me, we’ll find a way out," he said.

This wasn’t an isolated case.

In another part of the city, a facility listed by KMPDC as "no longer operational" greeted us with a large, active pharmacy at the entrance.

Right inside, a clinic was operating openly, with a list of services posted on the wall. Clients walked in and out freely.

Despite the official closure, the facility continued to operate under the same name, with no attempt to conceal its activities.

No valid licence

According to KMPDC records, it had been shut down due to a lack of a valid licence, the absence of qualified personnel, and a finding that the facility was not operational at the time of inspection.

A third clinic, flagged for substandard infrastructure and lack of qualified personnel, was also fully operational—a steady stream of patients walked in and out as if nothing had happened.

There was no sign indicating that the facility had been closed, and the general public seemed unaware of what “substandard” actually meant. For most, regulatory issues weren’t a concern—all they cared about was receiving treatment when they needed it. And yet, this was only a few days after the clinic had supposedly been shut down.

Out of the 376 facilities KMPDC announced as closed in Nairobi this year alone, The Eastleigh Voice was able to confirm that at least seven were still operating openly. The actual number could be much higher.

Speaking to a medical practitioner who requested anonymity, I learned of a deeply worrying practice within the private health sector.

Borrowed licences

"Many of these clinic owners are not doctors," the practitioner explained. "They borrow licences from qualified practitioners. The names you see on the documents aren't always the people running the clinic. And since the license holders aren't physically there, they don’t care if the standards are poor."

This practice of "lending licences" makes regulation nearly impossible.

During inspections, many owners tip each other off, temporarily close down, or hide equipment. Once the inspectors are gone, the doors open again, and business resumes as usual.

Most patients visiting these clinics assume legitimacy from a white coat or stethoscope, unaware they’re often being treated by unqualified personnel in poorly equipped facilities unable to handle basic medical emergencies.

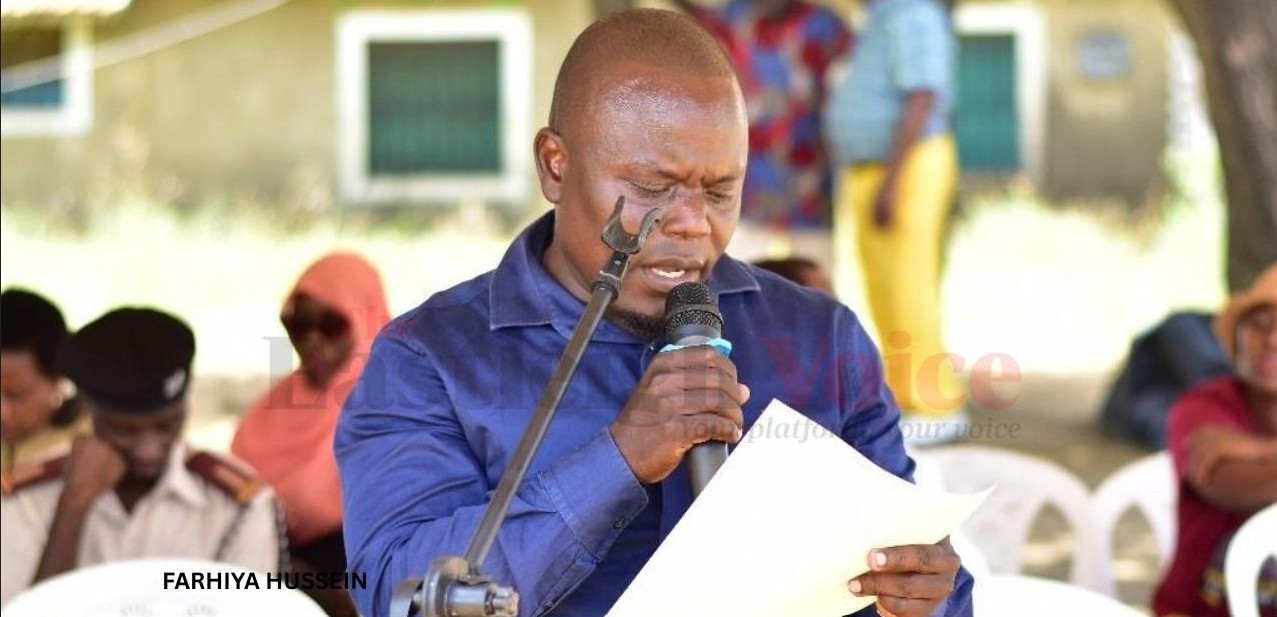

Many Nairobi residents, especially those without access to digital media, were unaware of the closures or what “substandard” meant; to them, the hospitals were open, affordable, and met their urgent healthcare needs. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Many Nairobi residents, especially those without access to digital media, were unaware of the closures or what “substandard” meant; to them, the hospitals were open, affordable, and met their urgent healthcare needs. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Despite multiple attempts, none of the health officials contacted were willing to comment on the issue.

Earlier this month, the Ministry of Health and KMPDC made headlines when they jointly announced the closure of 738 medical facilities across Kenya. Nairobi alone accounted for nearly half that number—376 facilities flagged for closure. The move was seen as a bold step in cleaning up the health sector. But on the ground, reality tells a different story.

There is a dangerous cat-and-mouse game unfolding between rogue clinics and health authorities. The result? Thousands of unsuspecting Kenyans are walking into facilities that should not even exist. They're putting their trust—and their health—into hands that often do not have the training, resources, or legal standing to offer medical care.

The spot check revealed that none of the closed facilities had any visible signage to inform the public that they had been shut down. The only indication was a list released by the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council—a document that The Eastleigh Voice reviewed, but one that the public likely never saw.

Unaware of closures

Most residents, especially those without access to digital media, were unaware of the closures or even what the term “substandard” meant in this context. All they knew was that the hospitals were open, accessible, and affordable—and that they needed care.

KMPDC also revealed that up to 80 per cent of clinics in Nairobi are run by unqualified individuals, often referred to as “quack doctors.” These operators frequently function under borrowed or fraudulent licenses, offering medical services without formal training or certification. The risk to public health, the report warned, is significant and growing.

In response, the Ministry of Health, in collaboration with KMPDC, launched a series of enforcement operations throughout 2024.

In a major crackdown in December 2024, authorities inspected 466 health facilities in Nairobi, shutting down 117 clinics and arresting 15 individuals for operating without licenses.

Earlier in the year, between February and August, a nationwide operation identified 811 illegal facilities, with more than 100 located in Nairobi alone.

Despite these efforts, the problem persists.

A late 2024 Auditor-General report revealed that out of 16,527 registered health facilities in Kenya, only 7,518 met full licensing requirements, leaving over 9,000 operating with invalid or no licenses at all.

Top Stories Today